|

AN INTERVIEW WITH MARC MCKEE Rewind to AWP Denver 2010: Marc McKee gave me a copy of his chapbook What Apocalypse? (New Michigan Press 2008). This brought me much joy. Fast forward to December 2011: Marc McKee taught me that shopping for butter can have life-altering ramifications. This brought me terror. Insightful terror. Beautiful terror. The best type(s) of terror, I suppose. Throughout my conversation with Marc, we discussed his first book Fuse (Black Lawrence Press 2011), larger issues of poetics, the shortcomings of our inevitable human mortality, the implications of gender reassignment, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, among other things and in no particular order. Throughout the interview process, I quickly learned that no question—poetry-related or not—would garner a simple response and we’re all the better for it. Marc, aside from being a cool, funny dude, provides some generous insight into the poetic craft, from catalyst (is that what we want to call it?) to the evitable chaos one incurs when experiencing poetry. Just a disclaimer: things are about to get real—too real—but you’ll be better for it. Fuse has this awesome way of making the mundane seem chaotic and the chaotic seem inevitable, and I was wondering what your approach was to style and tone when writing the individual poems for Fuse, and then herding them all into the book-length manuscript? I want to start by thanking you for such a generous reading of the poems. A lot of the poems that appear in Fuse are written under the spell of excitement and energy, or the disorientation of being romantically wounded, which is its own kind of excitement. My approach to style and tone was not to take a conscious approach to tone or style but rather to follow the thrill of language’s generative properties: the way associative logic coupled with an appreciation for what sounds good (or at least what sounds good to me) can kind of flood and keep flooding. Looking back over the poems now, there seems to be a good deal of lament. I think it’s a lot easier to write a sad line than a happy line, or a jubilant, celebratory line, but what I want out of a poem, whether it’s one I make or one I read is a kind of energy that resides in the poem and is released in each reading, and that calls for introducing and managing a variety of tones. I was conscious of that, so I was interested in countering the sadder tones with moments that might feel like eruptions of joy or even hope. Of course, I wasn’t thinking in terms even that sophisticated; my primary construction rule was more along the lines of: “That line was sad, what’s not sad? That. Okay, we’re stable, now what’s that buckling under us? That. What’s that in the sky leering down into the valley? Jokes? Ocean?” and then just insisting on that balancing act while whatever poem I was working on still felt like it had juice. The job of revising became to make certain that the poem itself was character, a body, differentiated enough from the other poems I thought I had written. This is still something I worry over. I’m sure it’s a worry I’ll never be done with until all’s done with me. Another important impulse that I feel like contributes to the realizations of style was the recognition that lyric poetry could be an engine of empathy and all the dizzying wonder and pain that entails. When you let yourself be subject to the lunatic lures of the material world and its expression in language, when you feel by turns hurt and despair or joy, my experience has always been that your awareness deepens. I don’t mean to suggest a privileging of the lyric “I” subjectivity, or a limited celebration of the speaker (and certainly not, cosmos forbid, the poet) to speak for the various others of the material world, which can kind of diminish those others. I wanted to try to let the lyric speaker’s sensory apparatus and the way language shapes the apprehension of a people- and event-filled world act as a vehicle to celebrate and mourn larger and larger worlds. Inside awareness like that, the objects your vision is normally calloused against begin to take on real lives. The way that Dean Young put it in an interview in jubilat from a few years back was that poems could open “clairvoyant portals of empathy,”—I will always be in love with that idea. When you are walking around after/in the midst of a romantic disaster at dusk, the cars people are driving around as they run their ridiculously mundane and vital errands just take on this incredible, thrumming pulse. I mean, you understand more immediately that they are risking their life to pick up cat food and a bottle of wine and butter. Butter. How many people have died going out for butter? When some dreadful accident has befallen someone you once vaguely knew, and you try to let yourself feel the actuality of what that might be, even if it can only be partial, the table you eventually come to sit at while you wait for the waiter to return with your pint becomes almost appallingly real, more so if some stranger has carved their initials into it. This state was for me the first association I had with being in the combusting engine of writing, really writing. Making poems from that state for me has always been about the objects that constitute the area of the moment just as it is about the emotion or whatever rhetorical arrows and eros you’re given to. Environment figured in words arranged in lines make the vehicle (and somehow I think this is connected to our 20th and 21st century imaginations being filmic—but that’s a tangent for another time). It feels natural to make the mundane—be it a table, stoplight, neon sign, tree branch, bird, loose brick, siren, low cloud, an overheard phrase, anything really—the material that is imbued with the abstractions and pre-linguistic inner weather you might be experiencing. I mean, the root of the word mundane itself is the Latin for world, and if there’s anything I’ve always been about, it’s getting as much of the world into my poems as I can, and as quickly as possible. If you try to get the world into your poems at the speed of perception, you’re bound to incur some chaos. I feel like that inevitability and the response of form to that inevitability gentle the world at the same time it challenges and enlivens us. To take another run at this question, it’s probably clear in the older poems of Fuse that the style and tone finds some if not most of its antecedents in poetry I was reading as I first became serious—serious… would engaged or invested be a better word?—as a writer. Of course, it doesn’t make sense to talk about style and tone without talking about the stylish, tone-rich people I was influenced by at the time (where “at the time” means “between 1998 and 2005”), many of whom of course still are huge inspirations to me. If I really started talking about them, we’d be here until the internet was almost over, so I’ll just mention quickly the guiding lights. I was, early in my experience as a novice writer, introduced to the New York School, particularly Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch, as well as people like James Tate, Mark Halliday, Mary Ruefle, Yusef Komunyakaa and a host of others. No one, however, can really match the effect that Dean Young and Jason Bredle have had on me and my work. Discussing fully their influence on me would entail a whole other interview; I’ll just say this: the first time I read Dean Young’s poems I felt like I was waking into a kind of kinship I’ve not fully experienced before or since in poetry; it was kind of the equivalent of hearing a band or musician that’s absolutely new to you and so immediately familiar that you feel like someone is making their music out of your own brain. I felt as I was reading Dean’s work like I was reading my own imagination, speaking from the future. Jason was the first person I met my age who I felt was a poet, and his friendship and his poetry have been important for me for many years, mostly because he is a great friend, but also because I think his poetry is better, funnier, rangier, and more dynamically experimental than mine, and that’s been a constant inspiration. Because of who I was reading, and how naturally those poets shifted tone or tried on new styles, I was lucky enough to feel invited to the party I never knew that I always wanted to go to. That party’s got monkeys and airplanes telling each other jokes, a fully stocked refrigerator and a good liquor cabinet and you can talk about Rilke, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or dance to someone’s laser pointer all in the same 5 minute conversation without being made to feel like that combination of impulses and loves are in any way strange, at least in an alienating way. Now, all of the things I just mentioned are brimming with a plurality of tones (especially BtVS). I had a naïve sense of this from the time that I first started writing seriously, I think; maybe my sense is still naïve. Maybe that naïveté helps, or that “knife-té,” as Jason Koo put it in one of his poems, when he phonetically transcribed one of Adam Zagjewski’s sage, calm exhortations to us as students. Making all the poems I’ve been writing for the last 13 (!) years into a book was just a long, long labor. The earliest incarnation of Fuse as Fuse is probably around 2002—I think that perhaps 10 poems are left from that incarnation, which would eventually become my master’s thesis. The title helped, though. Originally, I wanted to call the manuscript How to Stitch Flame, and was cautioned against it by the smart, perceptive Michael Dumanis, who I was fortunate to meet at the University of Houston. Since then, the meanings of the word “fuse” began to seem like properties of poems I thought should be included. One of my earliest fascinations as a writer was to try to figure out how to get as much into a poem as possible, and yet have the poem move as quickly as possible; this probably stems from some childish notion of what it takes to soar. The idea of a fuse being lit and thus emphasizing the finite amount of time one was given was important, as was another meaning for fuse, and the definition in particular that I found in a dictionary my grandfather gave me: to stitch by applying heat or pressure. That made the title Fuse feel true to my original creative impulses, and once that framework helped provide a guide, I began arranging around a faint narrative arc that I can sense and that is important to me but that is probably only apparent to a reader who is interested in taking the book apart and trying to figure out what the connections between the sections might be. It’s probably enough to say that I’m trying for a sensibility of the speaker that becomes less and less involved with how self-important the speaker’s local emotional, psychological state is. Instead, I want the “I” to move toward a larger understanding that whatever sensual and intellectual contact the speaker has with the world and its inhabitants generates a deeper and deeper empathy with all the other creatures hobbling or leaping around in their own terrestrial and extra-terrestrial orbits. Naturally, though, I count myself lucky if I can just get a poem to sound good. Throughout Fuse, you take an interesting approach to syntax, the line, rhetoric, and other linguistic acrobatics. For example, you often use short, fragmentary sentences followed by long, winding sentences, you verb nouns, you incorporate quite a bit of dialogue (italics), etcetera. Could you elaborate on the craft-based decisions you make when writing a poem? I’m happy to know you feel like my various approaches are interesting or even acrobatic, rather than opaque and/or deliberately obfuscatory. I feel like at this point, “an interesting approach to syntax” is every poet’s birthright. Maybe it’s even a responsibility no of course it’s not a responsibility. If you take a glance at the tradition, you’ll get threatened—or is that aggressive seduction? So hard to tell!—with its riches of approach. It seems that there is some kind of pressure on us at all times to validate whatever time a reader may be taking to read the poems by making the poems interesting experiences. The poems that I read which are manifestly interesting experiences and produce in me new energy are always poems that have new ideas or new ways of saying old things, wilder turns (or viler terns) that balance the tensions between sound and meaning. Or word order and meaning. Or line length and sentence length and meaning and doubling and tripling their entendres. One of the easiest ways to start doing that for me is to mess with syntax, and one of the flashlights in the dark mansion of syntax messing-up is Shakespeare. The thing that I realized about Shakespeare—and I’d like to point out that I am no expert, just an admirer and hopefully, sometimes, a thief—at some point is that he doesn’t always need to mess things up quite as much as he does. There’s a really great moment in the fun documentary Looking for Richard where one of the actors that Al Pacino is interviewing describes the difference between how Shakespearean characters speak and how people usually speak. He says (and I paraphrase): “Where we’d say ‘Hey you. Go get that thing and bring it to me,’ Shakespeare says ‘Be Mercury. Set feathers to thy heels and fly like thought from them to me again.’” Ask anybody: I’ve never been one to embrace the shortest distance between two points, conversationally, and I have a great affinity for the way Shakespeare does things. There are perfectly serviceable ways to communicate information, much simpler ways than he often takes. But the great thing about the plays is that you have people demonstrating those simple ways of communicating information right alongside people who recognize that words make reality and they can use that to their advantage or suffer the consequences of that being the case. Shakespeare, for me, alters the way weight is distributed in speaking, and thus how it is delivered, how it arrives. This is a result of knowing the easiest way to communicate the simplest thing, and having an ear for what a more musical way of saying a thing is. It’s connected to how beats or stresses work in a line to create a rhythm and how the very next line can change that rhythm. It’s also connected to the array of punctuations we have in our quiver. I feel like every punctuation has a different time: comma, period, semi-colon, colon, dash, et cetera: these are all ways to shift the sound a poem makes and when, and line breaks (and different stanzaics) build on these variable pauses (like rests in music… and that ends my knowledge of sheet music) to provide poets with more opportunities to elaborately introduce the reader to the weirder and not weirder musics that contemporary poetry is after. Of course, the more words you use, especially if you’re after a new syntactical order for them, the more chance there is to produce confusion and multiplicity of meaning, the ambivalence of language. But I sort of love that—we have to make everything up all the time anyway. Poetry gives us the opportunity to make it up differently all the time, whereas if you’re driving an ambulance, you want to do it more or less in the most efficient, safest way you possibly can every time. In a way, I feel like the love I have for certain bands and certain hip-hop artists also spur me to experiment with how and when the information loaded into the sentence and broken into lines reaches the reader. The problem with me, of course, is that is just the beginning of my semi-untrained thought about craft. I should mention that contemporary music, and hip hop in particular have also served as inspirations and educations in code-switching and finding ways to both compress language and make it do more work as elegantly as possible. Although sometimes not: sometimes you need a Mack truck to crash into a china shop in the middle of the night. I feel like I’ve learned a lot from my contemporaries, friends and strangers, about how the multiple ways to make words/lines/poems work, when you need blunt instruments, and when you need balletic grace, and when you need blood, and I’m sure I’ll keep on learning. Right. Better to stop now, before I start saying something backward about poets who are still alive. Again, though, as far as the craft-based decisions that I make while writing, I tend not to worry too much about anything except trying to make something that sounds good or moves quickly or produces moments of impact. Maybe my inclination to include italicized bits of dialogue is a hat tip to what by now is the expected appropriation and re-purposing of fragments put forward in service of new wholes. In the poetic tradition, our contemporary processes certainly have roots in the explicit practices of the Modernists, but is already at work in early Modern periods and most likely even before. Of course, the most pervasive contemporary example of this cobblery has to be the incredibly innovative forms and processes hip hop made explicit in its composition—but that’s still another interview. A long time ago, in a conversation or 12 that we were having about poetry, Jason Bredle and I arrived at what I at least think is perhaps the only essential rule for writing poetry: never be boring. Messing with syntax is just one easy tool for trying to adhere to that rule. While revising, I’m even more intent on making sure I’m saying something in an interesting way than when I’m initially composing, where I’m usually just trying to follow energy as far as I can, or, again, trying to get the poem to go as fast as it can. Also, there are jokes.

I’m addicted to reversals. When I was little, running around on the shimmery-with-heat playgrounds of my youth, there was a thing some kids used to do with see-saws, which someone else would call a teeter-totter (both words, obviously, are poems). Beginning at one end, they’d walk to the center and toward the end that was in the air, until the side on the ground began to rise. Then they’d rush back toward the end, trying to balance, to keep both sides in the air. Some of the more daring would rush to one side and rush back to the other side, to see how far they could go to one side before going as far as they could on the other while still keeping the trembling see-saw/teeter-totter balanced and off the ground. Sometimes I think that the impulse which led us to do that as the one that animates the speaker(s) of these poems. I really want to get as far to one extreme as possible before going to the other: I think it induces a kind of flight, or maybe only the sensation of flight but sometimes that’s enough. I love the idea that someone reading the poem could get the same kind of lift from reading a reeling poem that lists back and forth like a boat in a terrible storm, because aren’t we all boats in a terrible storm? Yes, and sometimes when we’ve kept from capsizing for long enough we are released, floating towards shore with the charcoal sky melting away and scars of sunlight beginning to dry our clothes. Any misleadings I have tried to set up as catapults to the cognition that everything is so much bigger than we think it is—I hope no one thinks I’m trying to trick them. There are a ton of recurring themes: the ineluctability of mortality, the inevitability of disaster, the value of the creative act. The poems want to be able to bear weight and make light of it, many of them are an exercise in forms of levity reacting to gravity, whether that means word-play as a defense mechanism, a vehicle for giving shadows the slip or actual jokes. I hope to never get over the incredible nature of the phenomenal world and the invaluable gift poetry has for making shapes of chaos. I really like the word ineluctable for some reason. Recurrence itself is kind of a recurring theme in my work. There were some deaths of the sad kind that inform a few of these poems, and every death of the sad kind is a reminder of our own inevitable finitude, although so is every sunset, so is every fallen leaf, so is every meal. I first came to Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” through the movie A River Runs Through It, especially the final lines, which the character of Norman recites with his father, and though I don’t have any Intimations of personal immortality, there is something comforting about the notion that while one can still look, one can look through death. We can lay it aside in dozens of ways, we can acknowledge it or fear it or try to ignore it, but our awareness of it should absolutely make everything that lives for us bloom so wildly. For awhile there, I couldn’t turn on the internets without seeing a picture someone had taken of a meal they had made. How wonderful and sad that is. Many of the poems here are the poems of a younger poet than I am now, and the burgeoning awareness of mortality is just beginning to thread into the consciousnesses of the speaker, though even one speaker is many. One of the tensions I’m trying to evoke between the beginning of the book and the end of the book is the inevitability of disappearance and how, inevitability be damned, we are inspired to make appearance over and over. It’s like the boats we are have a giant hole in the bottom but instead of bailing out, we’re bailing beauty and stuff and life in to fill the encroaching nothing. Take that, nothing.

I had in mind in titling the poem that one would assume both. It’s interesting that you see it as landing rather than breaking apart and thus crashing. Maybe it’s just crashing as gently as I can let it. I can’t help but think of that Revolutionary-era flag (which I saw countless times growing up in the Bicentennial memorabilia book someone bought me as a gift when I was born) is a snake in different sections which reads “Join or die,” which also reminds me of the pun that’s attributed to I believe Benjamin Franklin: “We must hang together or surely we will all hang separately.” I envisioned an airplane of my own experience chopped up in sharp curves in a remote place. By now, I can’t remember if the idea of that just became more and more real to me or if I actually saw news footage of a crashed airplane separated into pieces—and the decision to make “Serpentine Fuselage” the title of a poem that had originally been titled “How To Do Almost Everything” came well before Lost, so it wasn’t that either. Whatever the case, you’re exactly right to see it as one poem broken apart into 14 pieces. Originally, I had hoped for the book to reflect that the poem had been cut from being one continuous columnar enterprise into the same linear arrangements, just on different pages. It was not to be, but ultimately, I’m happier for how it has turned out. What we’re left with is the weirdest page breaks, and these feel like exceedingly (blessedly) weird stanza breaks for me. Like a lot of my poems it started out as a long, single-column double-time trek down the page. I actually started writing it in a bar in Bloomington, Indiana called Bear’s Place. I’d just gotten finished watching Three Kings, and something about the burnt husks of Iraqis gazed on by the characters as they’re on their way to try to loot some gold from one of Saddam Hussein’s bunkers…—I don’t know what it is about me, but often I have to rely on something artificial to be the vehicle of catharsis. Like, whatever the verb of catharsis is, I can’t that merely by reflecting on my own experience. It takes being given some kind of artistic gesture, some kind of made thing that essentially amps a particular experience or emotional tenor that calls me out. It’s a less severe version of something Mark Doty describes so beautifully in the absolutely heart-ravaging Heaven’s Coast. If you know the book, this is towards the end. After an awful allotment of tragedy has occurred, Mark’s getting a massage, and the masseuse, if I’m remembering this correctly, asks him about this particular area of his back and warns him about what’s going to happen if he properly massages it. When Mark tells him to go ahead, all of the sadness and heartbreak just floods out. Well, I didn’t have anywhere near the tragic sadness to deal with what he did, but I was sad, and this movie just hit the right note. I was watching it in the back room of this bar, and after it was over, I sat in a booth with a pint or however many I wound up having and just filled napkin after recycled napkin with these lines. Every time I’d hit a spot of stopping, I’d sew in some bit of song or poem or something else I’d heard recently, and this got me to go on. For years I typed out that poem and kind of curated it until I got it to the place where I thought I wanted it. I’m sure this doesn’t sound weird to other writers, and in fact I remember hearing Marc Maron say something similar to this in a recent WTF podcast of his where he was talking about the evolution of jokes in his stand-up material. He was talking about how sometimes it takes years of massaging something you know is not perfect, but worth the effort, and then there comes a moment when you’re just precisely inside it and you make the perfect adjustments, and the thing-as-it-should-be crystallizes. It’s rare (and I’m not saying that “Serpentine Fuselage” has found its perfect form, just as near as I can get it), but when something like that or even kin to that feeling happens, it’s exhilarating.

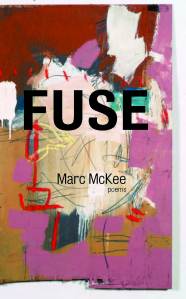

You know, there were never really any other serious contenders for the cover. Before I had any idea about Rob Funderburk’s work, I had been vaguely considering a photograph I’d taken of an old television perched in a fuzzy, pink armchair set out in our back yard, grown over with flowers and morning glories and desiccated raspberry plants and who knows what-all. But I knew that was a placeholder; it just didn’t really generate the right kind of energy that I wanted from a cover. I got really lucky the first time I got to have a cover, for my chapbook What Apocalypse?. I just found a photo of the All Souls Procession, an annual Day of the Dead procession in Tucson I knew there would be wonderful photos of, found out who took the picture, got in contact with them, and was delighted when the photographer cheerily complied. For Fuse, I was completely at a loss—I thought for a while I should just have some simple stock photo of one kind of fuse or another, but that also seemed lame. Then, my wife Camellia came across Rob’s work, who she had known from a while back or through other people, either via Facebook friendship or some similar coincidence. She was pretty excited, because she knew I’d been anxious about finding something and she is well-acquainted with my tastes. Sure enough, when I took a look at his work, I was struck dumb. It’s gorgeous. When I came across the painting that I ultimately asked Rob for, I got really excited; it felt very right to me. The title is, well, it’s untitled, but the caption on his website is “LOA Series #1, Untitled.” It’s got this cock-eyed symmetry that seems to proceed out of some kind of uneasy truce/tango between eruption and stitching that I felt was entirely companionable with the way I felt about the poems in Fuse. I need to shut up before I just drip syrup all over this interview, but I was so happy with the way the cover came out, and I’m totally grateful for Rob’s extreme generosity in not just allowing us to use the image, but for also giving us some very excellent design suggestions, which have been incorporated into how it looks as a real thing in the world. Astonishing. I still can’t quite believe it. For me, it serves as wonderful entry point into the book in a couple of ways. First of all, it’s got dashes and sashes and explosions and boxes, it moves the eye up and down and across the page and the paint is both its own event and decidedly in relationship with all the other paint: it’s the visual rhyme for some of my ongoing aesthetic desires, it’s like what I think about poems! and it (like me) is also in part the product of abstract expressionism and the New York School. I was also very happy that the layout resulted in the photo of the painting being reproduced on the cover. If you look closely, you can see the pegs or nails that have been used to hang the work. It feels to me like the cover manages to foreground the object-ness of the piece as well as the get-lost-in-it gorgeousness, rather than just blowing up a detail and encouraging you reside in the pared-down, discrete beauty of a single element. I love how in a museum or on the side of the road or in the middle of a book of poetry you can come across something that claps you awake and washes over you and pulls the pin on a thrilling, interior grenade, and then it just pushes you into something else. Some sunlight, maybe, or towards the iced tea or excellent lips of your companion, or a memory of the first time you saw a motorcycle. Part of what I want my poems to do is accomplish that: to get your attention, to zip through to one or seven or eleventy thrilling destinations and then ask you to fly off down your own corridors and meadows. I wish my poems could wave. Maybe they should break bottles of champagne near the end and then shut up so you can get on with your voyage.

Well, no taxonomy is perfect, but I think that you’ve come up with a productive way to start thinking or coming to terms with distinct impulses of making, and without suggesting that one or the other is the obvious Artist’s choice (versus the Amateur’s choice). I guess if I had to answer definitively then I’d not answer at all. Since I don’t have to do anything definitively, however, I can start out by saying that I gravitate toward the externally-oriented (and orienting) pole of your binary. I’m not exactly sure why it is that I don’t have any particular interest in laying bare my insides—maybe it’s a mixture of lucky upbringing and abject fear that what’s inside me isn’t all that interesting or useful. Whatever the case, I’ve never seen the making of poems as an exercise in the expression of an author-bound self as an enterprise I wanted to embark upon. This is not to say that my poems don’t (in their own particular and peculiar ways) unfold from whatever inside I’ve got: inside’s where I’ve got all my musical instruments and firecrackers, it’s the recording booth and the mixing boards where I get to make stuff. But I don’t try to go in and drag a polished me out. Instead, I try to go in with all the world I’ve dragged in kicking and purring, and I set about marrying the real I’ve reeled to the particularities of sensibility I feel go into the making of a speaker, and that speaker becomes a way of shaping, of delimiting all those materials. In that scenario, I guess revising would be me coming in and trying to objectively listen to the poem and fix some of its more abject unsightliness or stupidity, though more and more I appreciate wrong turns and imperfections. Speaking of binaries or poles like the ones you have articulated, I should mention that I’m not really against them, so long as they are a beginning dialectic from which poetry inevitably diverges. That’s the way I try to talk about poetry in the classes I teach, as well, though I’m usually interested in figuring out what the students received notions of poetry are and trying to challenge those. I think that this resistance can have either the effect of the student tossing out bad or under-considered assumptions and liberate their creativity or they can resist in kind, which has the benefit of pushing them back into their own assumptions and creating new reasons for their assumptions and practices. Either way, the effect is an intensified relationship to writing, to the exhilaration of making. It can be productive in a workshop to begin with binaries, so long as you don’t stop there. I mean, as soon as you say something is either hot or cold, then you’re going to have someone else say it’s cold or hot and another person say it’s lukewarm, and still another person say it’s actually more purple than carburetor, but it’s nothing compared to French fries or a wedding. People’s insides and outsides are so divergent and plural that laying claim to either impulse is just the beginning. Fortunately, often the beginning is where you want to be. Except when it’s not. And then there’s the other position, and so it goes. See how fun this is? You give me two things and tell me I could be one or the other, then my natural resistance to being pinned down gets charged up and I have to start using my imagination to generate other things to be, which is really the point of coming to any realization whatsoever: to prod us beyond what’s gone before, into the new, into, as Frank O’Hara put it, “refreshment.” Ah, refreshment. So great. Of course, the word “catalyst” is interesting. It’s one of those words that feels so expressive that I pretty much expect to experience something immediately after reading/hearing it: to me, “catalyst” is a catalyst, and that’s about as close as I can come to saying what the catalyst is for making poetry. Fascination with the word, the word that follows the first word, and the energy engine poems make from slamming a bunch of them together in ways familiar and strange.

I love this question. I can’t even begin to assess all the implications, but it makes me want to write a whole new version in which I am a woman, or visit an alternate universe in which I am a woman writing these poems. Of course, there are two ways I could take this: 1) how would the poems be different if the speaker identified as a woman, and 2) how would the poems that I’m responsible for be different if I identified as a woman. Let’s treat the first, speaker-oriented question first, because it’s easier. There are several games going on with the speaker in these poems, though they are fairly simple games; usually, Fuse relies on the notion that the voice in the poems indicate a singular speaker that sort of resembles me, though I suppose that some of the work could be just ambivalent enough that the speaker could always already be a woman. Maybe. I’m sure there’s some heteronormative coding that is part of the DNA of the work just because of my limitations as a human, which I hope have lessened over time; I am trying to contain and connect more multitudes. This question reminds me of when I was a skater, years and years ago, at the beginning of high school. I read a short story in a Thrasher magazine that followed a skater in some more or less sci-fi endeavor to skate a concrete pipe with such speed that there was some kind of time travel effect. My brain was so yoked to my assumptions about the skater and the time travel aspect that when it was revealed that the skater in the story was female, my mind was double-blown: 14-year-old Marc’s first education in the assumption of male (not to mention white) privilege. My work over the last few years has begun to more adamantly take up some of these questions, although my experiments have led less to the poems having an explicitly political function than an aesthetic aim for richer, more diverse approaches. After studying dramatic monologues and persona poems from Victorian and Modernist poets to the incredibly diverse speakers on display in English language poetry as well as European poetries that we (most of us) read in translation, I’m more acutely aware of the plasticity of what we call the speaker (as well as attempts to void poems of their speakers, whether that’s in L=A=la la la experiments or in various other strategies from the avant-garde quiver from the 20th century or on and on it goes). During the period in which the Fuse poems were being written, I was flirting with the distances and ironic gestures that could be enacted under the banner of the “speaker,” codifying autobiographical materials, changing names, misquoting, switching pronouns, and generally trying to run pleasantly amok, while at the same time remaining somewhat conversational. I wanted people to feel like they were in awesome conversations, but without feeling like they had to be in conversation with a singular, self-important speaker (although, going on at this length, I wonder if anyone’s really going to buy that intention). It doesn’t really bother me if people associate me with the speakers; most readers of poetry, no matter their sophistication, often do that with ambiguous but seemingly singularly-voiced lyric speakers, unless some blatant clues direct them otherwise. The secret is always that no one is right: no poem can really claim to dispense totally with the aesthetic, creative, and probably particularly physical, psychic and emotional materials empirically associated with its writer/author. If I were to take this question as intending to ask how the book would be different if I, as the author, were a woman, then the answer becomes much harder to supply. Partly this is because an answer to that question requires a bit of speculation on my part, and partly this can be put down to the ultimate failure of any particular empathy to be complete. It seems pretty likely to me that no one reading this interview will need to be reminded that our culture treats men and women differently, and by differently I mean to say that historically and traditionally our culture treats women with oppressive inequity. Women are on a long list, of course, along with people of color, ethnic minorities, GLBTQ humans, and once you consider economic inequality then you’re really just in the tall grass of early 21st century America, doing the best you can to recognize the uneven difficulties everyone faces in being and trying to persist. I’m a white, heterosexual dude, and I come from what I would identify as a middle-class background. There are privileges I’ve benefited from in my life that might still be invisible to me, try as I might to recognize them. I don’t think it’s going too far to suggest that if I was a woman and I wrote these poems, even if the only variance was the switch in gender, that the poems would be totally different. Even if the experiences, the emotions, the aesthetic and artistic inspirations, the television, movie, and music habits, the socio-economic and family background, the friends, teachers, students, and strangers: even if they were all the exact same, the poems would be different. I can’t really say exactly how they’d be different, I just know they would. You mediate the world through your body, whether it’s the external world apprehended in your physical senses or the internal world you carry around made of events and experiences which have included you and are forged by your emotions, thoughts, dreams, the debris of memory, and internalized educations (and I do for sure mean that plurally). In our culture, there are different expectations, assumptions, reductions, cosmetic imperatives, and on and on assigned implicitly and explicitly to gender, and to pretend that my poems would be exactly the same if I was subject to a whole other menu of expectations by being born someone other in any major way seems pretty silly. That said, I can only speculate on what those actual poems would be, and that could be fun, although also painful. The good news is that poetry, by being mutable, plastic, and subject to the development of the humans and their appetite for new refreshments and investigations can be an agent of liberated, creative and expressive empathy, rage, sorrow and joy. It can shake day-to-day communication awake and tell it to dream better, can tell us who we were, register who we are, and imagine who we can become; it’s such a serious responsibility that we better take it as lightly as possible, and have as much fun as we can. Marc McKee received his MFA from the University of Houston and his PhD from the University of Missouri at Columbia, where he lives with his wife, Camellia Cosgray. His work has appeared in journals such as Boston Review, Cimarron Review, Conduit, Crazyhorse,diagram, Forklift, Ohio, The Journal, lit, and Pleiades. He is the author of What Apocalypse? (New Michigan Press, 2008), Fuse (Black Lawrence Press, 2011), and Bewilderness (forthcoming, Black Lawrence Press, 2014). --- Eric Morris teaches creative writing at Cleveland State University and serves as a poetry editor for Barn Owl Review. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Laurel Review, Pank, Post Road, The Collagist, Anti-, Devil's Lake, Weave, Redactions, and others. He lives and writes in Akron, OH where he searches (mostly in vain) for a way to lift the curse of Cleveland sports.

|