|

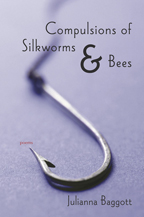

In her third collection, Julianna Baggott attempts to steer a craft that might, in less skillful hands, result in a monstrous wreck. The main subject of Compulsions of Silkworms and Bees is poetry itself, and many of the poems offer titles like this: “Q and A: Do you simultaneously submit?” or “Poetry Despises Your Attemptsat Domesticity.” Of course, the idea behind this book, a volume of poems about poems themselves, is nothing new. But these lines avoid the Been-There-Done-That Fallacy by radiating in a way most don't, showcasing Baggott's lush sense of detail. And by relegating herself to one subject, Baggott ironically affords herself great range within the borders of her canvas. Fittingly, the book begins with an address to the reader:

Baggott follows up that opening act of flattery with a persona poem exchange between Poetry and the Novel, and when Poetry says, “We're twins, but, in fact, I think my father wasn't yours— / newsman, bettor, drunk,” the Novel replies with one of those “small, shocking acts of tenderness” mentioned before:

And throughout this book there's a momentous, irresistible playfulness. Several of the poems answer questions. One, “Q and A: How is it that poems can just fail (the abridged version),” replies coyly:

But there's also a certain amount of frankness to the voice Baggott employs in many of the poems, and perhaps never more so than in the conclusion of one of the book's best pieces “In Response to Poetry is a house with many rooms.” In that poem, and others along the way, Baggott exemplifies a tone that makes this book a must-read, in taut, biting lines that surely afford her the last word on the subject of her choosing:

--Jay Robinson

|