|

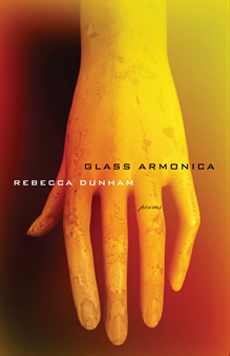

Glass Armonica

Rebecca Dunham

Milkweed Editions

2013

96 pages

The poems in Rebecca Dunham’s Glass Armonica are tight in both form and feeling. Not a word is misused, and no comfort is left for the reader as Dunham’s speaker dives into femininity. These poems are about the female body and mind in varied forms of imprisonment. The speaker may be enveloped in winter or living in a sanitarium from one page to the next, but Dunham’s work flows beautifully as this multifaceted tension develops.

Dunham’s poems are at their most striking when the directness of the speaker contrasts the horror of the situation. In “Hemispherectomy,” the literal exposure of the speaker’s brain makes her omniscient: “Face covered by the long / sterile drape, I could be anyone. / This will make it easier, / he thinks.” The speaker concludes by describing her brain as “an infant / who is bound to disappoint,” knowing she will be deemed unsatisfactory in some way. This is an important tension: the women in Dunham’s poems, often considered the “weaker” sex, prove their mental dominance, which is ironic considering the history behind the “Glass Armonica” sequence.

Dunham’s notes are chilling—these poems still haunt me—regarding ideas about “hysterical” women from Franz Mesmer and Jean-Martin Charcot. In “Augustine, at the Salpêtrière, 1875,” Dunham gives a voice to one of Charcot’s famous patients: “The photographer catches it— / How my physiognomy expresses regret… / Abundant vaginal secretion.” Here, Dunham shows the reader a woman at the height of vulnerability and objectification, and these images are necessarily bothersome for the effectiveness of Augustine’s second appearance in this sequence in September 1880:

Each spell is reenactment, is rehearsal.

I play both roles in turn: push myself

down, arc-en-cercle, rip my own gown free.

A release. How else to flee Salpêtrière

but as a man, to set my skin unkeyed—

The poem ends in this moment, mid-escape, and this idea is central to the power of these poems. There is victory for these female speakers in their mental fortitude despite being far from any position of power. Augustine’s escape from Salpêtrière seems to happen in a flash, as the lack of grammatical sentence finality suggests, and Dunham’s use of an em dash here similarly implies the breathlessness of hysterical behavior. Style and tone continue work harmoniously throughout this collection.

There are moments in Glass Armonica when Dunham explains what it means to be a woman regardless of time and circumstance, like here in the title sequence: “The horror is not the sewing on. / The horror is who will unfasten you” or here in “House-Tree-Person,” another poem that makes use of psychological experimentation: “Like a chest—locked— / my breast’s orchestral bellow / and beat.” These lines express the thrill and madness of both isolation and proximity, what the female body looks like and how it feels for a woman to allow someone else to open it—often, in these poems, against her own will. Dunham’s poems are so gripping in this way, and she is able to effortlessly insert us into another person’s life.

The final line of this book stands alone in “To Winter,” an ekphrastic piece where I like to think one of Dunham’s female speakers is free in the natural world: “To feel you untie the knotted throat.” What a beautiful hope to be left with after the cold, sterile environment impressed on us by many of these poems. This speaker wants to feel what it is like to be opened so the pressure of being might alleviate. After reading Glass Armonica, you will hope for this sensation, too.

--Sarah Dravec

Sarah Dravec is a graduate student in the NEOMFA in Akron, Ohio, where she studies poetry. She is a poetry editor for Barn Owl Review. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in And/Or, Blast Furnace, Bone Bouquet, Dressing Room Poetry Journal, *82 Review, and others.

Also by Sarah Dravec:

Review of Vivarium by

Natasha Sajé

Review of Phrasebook for the Pleiades by Lorraine Doran

|

|