|

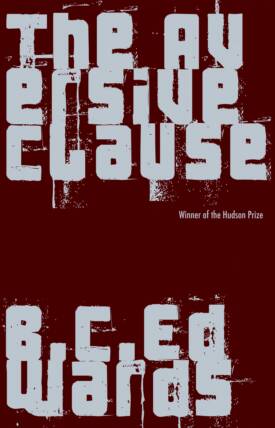

Sometimes words take on negative connotations that aren’t always justified. So when I say the stories in B.C. Edwards’s debut short story collection The Aversive Clause feel familiar, I mean so in the most positive way. I mean it in the way I feel after I read them. Sure, there is a kinship, a sympathy, a sense of knowing to these characters, but it’s more than that. After reading a story, I would set the book down and think to myself, “Damn. I wanted to write a literary story about a dinosaur, I just couldn’t figure out how.” B.C. Edward’s has figured out how to write good stories about dinosaurs, zombies, doppelgangers, and angels. These are not pulpy genre stories, though. Part of the way he achieves this is his use of frames. Whether it is epistolary, chronologically reversed, or relating a recipe for tuna salad, it is the perspective of these stories and their characters that makes them so interesting. In “Eugene and the News,” the protagonist is tracking a Tyrannosaurus Rex across the desert with a major network news team. The reader follows Eugene via letters to his mother as the dinosaur becomes increasingly aggressive toward the techies and talent. What starts off as silly becomes heart breaking as the simultaneous desensitization to the death of his coworkers and the sacred bond he forms with the dinosaur grow ever so slightly in each letter. That’s probably as good of a metaphor as any for how these stories work. While they aren’t all fantastical, they all have parallel plots and multiple character arcs. If a story isn’t about God running for president, it is about two homosexual lovers beneath the shadow of the St. Louis arch and the watchful eyes of conservative Christian cousins. What all these narratives have in common, though, is a sense of electrical tension—the smell of ozone before lightning snaps. In The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot, Charles Baxter talks about the reluctance of Midwestern writers to create a conflict in his or her story. Edwards makes his home in Brooklyn and has no such reticence. The reader is propelled through this collection because one never knows where the tension will come from. The collection’s first story, “Tumblers,” clocks in at only four pages, but it manages to keep the reader on edge because so much could happen. Will their cabbie find the party in time? Will the tumblers be too drunk to tumble? Will the mafia boss kill them for talking to his daughter? Each page a new question until the point where the guns start going off and the reader has to simply nod his or her head and say, “Yeah, something like that was bound to happen.” That’s not to say this technique of ever-ramping tensions always plays out well. The stories range from three to twenty pages, and in general the shorter ones feel a bit stiffer than the rest. Edwards hits his mark in the handful of stories that are ten pages long. The shorter pieces often feel like creative writing prompts that haven’t moved far enough away from the idea generation stage to be a full story. “Stop. Turn.” in particular never seems to shrug off its future tense writing prompt premise. Edwards’s writing style is clear and concise. He approaches his texts in a way that says either the language can be weird or the story can be weird. To have too much weird is to be confusing, and the reader never feels confused in this collection. Unsettled, disturbed, and disconcerted, but never confused. In place of fancy acrobatic language, Edwards becomes a connoisseur of metaphor and simile. In “Bigger than All These Buildings,” he writes, “We are all balloons far overfilled and shimmering in air that is far too hot.” In another story, “The long tail of cars sat like some black millipede.” The metaphors do the work of playing with language and setting the proper tone but never feel out of place. The book is so varied in its tales—apocryphal, dystopian, and domestic—that anyone can find what they’re looking for. As much as the narratives run the gamut of genre, the emotional spectrum the book covers is just as impressive. I never thought I would root for God to lose the presidency until I read The Aversive Clause. Jacob Euteneuer lives in Akron, OH with his wife and son, where he is a Barn Owl Review small press fiction staff reviewer, and a candidate in the Northeast Ohio MFA. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Hobart, WhiskeyPaper, and Foliate Oak.

|