|

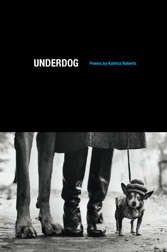

Katrina Roberts begins Underdog, her fourth collection of poems, with a masterful overture introducing the themes and concerns that continue throughout. In “From Po Tolo to Emma Ya,” an ordinary trip to buy postage stamps tilts in the plate of the poem to invite other dimensions. Everything connects— Dogon mythology, astronomy, Mexican immigrants, ancient Rome, and a young child’s toys: “to stretch like pink gum . . . to hold still all/a single moment has become” or could have been in the long string of time. Hallmark cards and gandy dancers, Spanish and Swahili rise through the lines of this long opening poem as if surfacing through layers of time, the historical as carefully resurrected as the frail evanescent moments of the present. Roberts’s poems are specific, imagistic, and visceral: a turnspit dog, for example, described as the “[s]ize of a small breadbox, rusty as a fox/ with a heartshaped snout, his eyes/ black marbles now.” Roberts writes accessible poems in a variety of line lengths and stanzas making a subtle use of sound. This is not to suggest her work is not complex. But its difficulty, its useful difficulty accrues through intricacy of connection rather than withholding. She offers a kaleidoscope that mingles vistas, a visionary telescope that can also isolate the particular of everyday. Her subject matter is vast, a word she considers early on. In “Ground Water, Enchanted,” she quotes a Chinese proverb: “A bird does not sing because it has an answer. It sings / because it has a song.” Here, mummies and the life-size terra cotta soldiers of Emperor Qin Shi Huang Di stand silent while the poet sings like Whitman surrounded by Facebook, ear buds, and references to Pliny. The book closes with a whimsical narrative describing the finding of Nanny Robert’s cursing pot (a real object) in nineteenth century Wales: What will become of us having touched this vessel, this book? What witching has come upon us? --Susan Grimm Susan Grimm is a native of Cleveland, Ohio. Her poems have appeared in West Branch, Poetry East, The Journal, and other publications. In 1996, she was awarded an Individual Artists Fellowship from the Ohio Arts Council. Her chapbook, Almost Home, was published by the Cleveland State University Poetry Center in 1997. Her book of poems, Lake Erie Blue, was published by BkMk Press in 2004. She also edited Ordering the Storm: How to Put Together a Book of Poems which waspublished by Cleveland State University Poetry Center in 2006. Recently, she won the inaugural Copper Nickel Poetry Prize. Her chapbook Roughed Up by the Sun’s Mothering Tongue was published in 2011. She is a poetry editor for Barn Owl Review. Also by Susan Grimm:

|