|

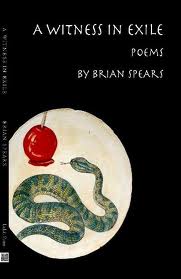

A Witness in Exile: “The Walk Home is Never Long Enough” The basic desire to reclaim one’s personal history for oneself (“I am where no one is a stranger,/ just misplaced family returned home”), given a freighted legacy of religious, even evangelical training and family involvement in same, are among the very human desires set for in this in many ways miraculous first collection. Imaginative sympathy may be thought to be a reflexive rather than thoughtful gesture herein, but the errors in this assumption would be many and vast. For starters, the speaker doesn’t so much take up the work of praise or even lyric self-creation, but rather that of imagining worlds for himself and his loved ones that define the bounds not only of religious historiography but of culture, and time. From “Sonnet for my daughter, age 14”: “The Krewe of Perseus you said and I/ imagined floats of gorgons and pegasi,/ purple-plumed Mardi Gras Indians,/ a brass band playing Gonna Fly Now,/ tiara-ed teens in LaMarque Ford convertibles./ First time I heard you play your flute was through/ your bedroom door; Kumbaya, my Lord/ shrill and piercing. I like to think I’d pick/ your tone, now warm vibrato, out of the crowd.” It is this and other poems’ focus on the addresses’ singularity and distinction from the sea of others or families constructed along ideological rather than blood ties which lends them their own singularity and import. This is indeed a speaker in exile, whose wandering and wonderings mark, irrevocably, the page: “ . . . I wonder, I wonder if I was wrong to search/ elsewhere for that which transcends, if soon the day will/come when my old family will be the only ones left standing/ strong for God in the face of the wild beast . . . ” For someone born into any religious or ideological shoe-horn wherein conformity is valued, the mere notion of self-invention (as distinct from serving a Creator) is to, in a sense, exile oneself. For this poet the real dangers inherent in the decision to leave the church (if not the fold) breed a form of self-invention that is at time quixotic (“I, a virgin, witless,/ unblooded, a fool’s grin slapped on”) but more frequently wild or artfully allusive, in poems that strip the motive for adopting personae to the core: (“I am sun and wind,/ am river rage and tide/ and the earth’s molten core”; “I wish I had hair like Absalom,/ weighing two hundred shekels . . . I would offer it up, sheared/ to the scalp.”) Postmodern readers know both writers and readers have been at war with the capital T-truth for decades, ever since modernism ushered in, with consequences that couldn’t then be seen, the notion of multiple valid perspectives as constituting “truth.” The speaker of this collection takes not just the fallacy of a totalizing Truth to task, but the notion (so critically derided it’s easily forgotten to constitute the lingua franca of whole states in the USA, a fact that rears back into consciousness only during presidential elections) of an all-caps TRUTH, as in, “ . . . a wondrous, witless witness/ sent abroad in missionary position . . . to spread The TRUTH!/ (in caps we say it, honest) TRUTH!” The poet’s tough love rather than scorn for those who think themselves not just in possession of the Truth but The TRUTH is instructive and often bears with it non-derisive humor, but is also borne of his unique legacy. Holy writ meets pop culture meets poetic consciousness meets familial ties, both religious and secular, in the deep South: A Witness in Exile challenges our very notions of what it means to take on the responsibility of a metaphysical commitment in the 21st century, as an heir to religious practice of any stripe, or not—and mean it. This book incubates and releases its own speaker into a world of his own making, showing the work—and art—of self-fashioning to be not only timeless but the bind that connects us all. From “Dental Hygiene in the Middle Age”: “ . . . even with the hole in the line,/ the gasp/ of breath. Taste of amalgam, smell of burnt/ drill, tooth, sweat beads from the lamp-heat,/ fingernails in armrest. I’m done. Unclasp.” ---- Also by Virginia Konchan: A review of It is Daylight by Arda Collins. A doctoral candidate in the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Virginia Konchan’s criticism has appeared widely, and her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Best New Poets 2011, Boston Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, the Believer, The New Republic, Notre Dame Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Jacket, and Poet Lore, among other places.

|