|

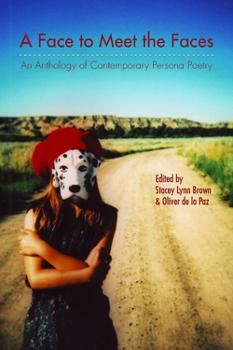

In A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry, editors Stacey Lynn Brown and Oliver de la Paz have collected a vast array of poems from some of the strongest voices in poetry today. Ranging from historical figures to fairy tale creatures and beyond, this anthology runs the gamut of what is possible in American poetry. In each section of the book, we are offered different voices on a given theme, but these voices don’t fit any expected specific boundaries. For instance, one of my favorite sections, “Fifteen Easy Minutes: Pop Culture and Celebrity,” ranges in voice from actual human celebrities to superheroes. You might think it wouldn’t be easy to sequence poems from such different viewpoints, but take the following poems in which our very humanity is revealed in the speakers’ struggles and desires. In “How She Didn’t Say It” by Camille T. Dungy, Ella Fitzgerald reflects on her life of song: I’m called In “Hulk Smash!” by Greg Santos, our speaker considers his actual life: Who Hulk kidding? Hulk not really so incredible. In both of these poems, we see the longing of something needing to be said that was never uttered, that was never part of the persona we saw or see on stage or in pictures. Fitzgerald struggles to merge her real life with her public persona (“It used to bother me when people I didn’t know / called me Ella they ain’t blue no”) and Hulk cannot live a normal life because of his size and uncontrollable anger (“Cubicles too small for Hulk, though” and “Hulk smash paper shredder!”). These speakers cannot live out the lives they want. Two other poems in this section, “Like This” by Frank Giampietro and “Man on Extremely Small Island” by Jason Koo, exhibit human longing in the strange or imagined. In “Like This,” the speaker is a man, Monsieur Mangetout, famous for devouring metal and glass. In the poem, these shards quench his desire to be loved: Later, he begins to crave more: The poem spirals into a catalog of what the speaker has devoured and ends on a note of longing: the speaker sees his reflection in his father’s new razor blades. In “Man on Extremely Small Island,” based on a Mordillo cartoon, we meet a speaker who imagines the island on which he sits to be a “gigantic woman” and that he sits on her kneecap. He imagines the geography of her body, but not her posture or How she came to be here, howI happened to wash up on her kneecap shore, why she never puts her leg down— these are questions I do not pursue. He is afraid that if he moves “a giant hand / will come whalebursting out of the water / to thwop me like a golf ball into the sea.” Later, the speaker considers the geography of his own body: Miracle. And all those years I asked He considers how he completes the island-woman on which he has landed: “And my sea-goddess, / she has no nose. Just a space where mine / can fit.” The speaker’s clothes start to unravel, just like any shipwrecked person’s. He finds a bottle with a message, “I’m alone, it said. Find me, find me. / I threw it in the water.” Do these speakers finally get what they’ve desired? Is one satisfied by the tons of metal and glass he embraces instead of parental love? Is the other satisfied by the island shaped like a woman, thinking he might never come so close to a female body? What do we want? How is it that we think we satisfy our desires and yet still come up short? Like Fitzgerald and Hulk, we need to utter what was never said. We need to pursue the reality of our lives, those pictures the crowds refuse to see. The beauty of the poems in this anthology, throughout every section, is that they remind us of what we desire and loathe, and from what we suffer. It takes putting on the mask of another person or symbol to speak to these things, whether it’s Calamity Jane at the grave of Wild Bill or the X mark on houses in New Orleans. These poems remind us of what we share. They remind us that we’re human. They bring us back to one another. --Julie Brooks Barbour Julie Brooks Barbour is the author of the chapbook Come To Me and Drink (Finishing Line Press, 2012). Her poems have appeared in Waccamaw, diode, Prime Number Magazine, storySouth, Connotation Press: An Online Artifact, The Rumpus, and on Verse Daily. She teaches at Lake Superior State University where she is co-editor of the journal Border Crossing. Also by Julie Brooks Barbour: Review of Fire on Her Tongue: An Anthology of Contemporary Women's Poetry |