|

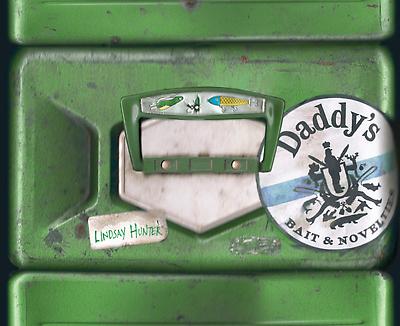

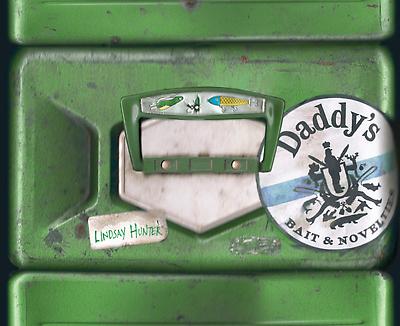

Daddy’s

Lindsay Hunter

Featherproof Books

2010

$14.95

217 pp.

There’s a line in the story “Tuesday,” fairly late in Lindsay Hunter’s Daddy’s, that goes “Behind her the sky was so blue it could’ve stained your finger,” and I’d like to think this line encompasses the spirit of this terrifying book. For some reason I want to say the stories in this book take place in the southern States. Maybe that’s because someone pronounces the word “fence” as “fayuhnts” (gosh!). Or maybe because this one freakbeast mutant baby from hell is named “Levis.” Or else, it’s that word, “daddy,” which just can’t help but keep popping up.

The stories in Daddy’s are twenty-four itchy, gurgly little gems about our connections to our loved ones, the way we feel, the way our bodies feel, the way our bodies connect, and the junk we do in and around and outside of our bodies. They are about how cursed we are from the moment we are spawned, from the moment we spawn, etc. They are about the messiness of life. There is a crunchy, sticky, frictional nature to the language, because Hunter is reflecting the tactile nature of the world her characters live in. This is a world meant to touch. These are bodies being pummeled and touched. The line from “Tuesday” indicates a world where something as ethereal as the sky can be smeared by our grubby, grabby hands.

The title makes sense if you think about how that apostrophe and that S create ownership. You are daddy’s. I am daddy’s. He, she, it is daddy’s. You will always be daddy’s, no matter what. You come from daddy. And the fact that it’s not called Mama’s.

There is gender-related commentary in here, for certain, but it’s the good kind, the kind that makes me shake my head and mutter, “Jesus,” the kind that makes me think I don’t even deserve to read this book.

There’s a particularly good story (though they are all quite good, great, indescribably powerful), “The Fence” (“fayuhnts”), in which a woman with a sexually abusive husband uses her dog’s electric fence collar to gratify herself. The first time this happens is revelatory: “The fence is invisible, but it’s there. I wind the vinyl part of Marky’s collar around my hand, holding the plastic receiver in my palm, and then I press the cold metal stimulator against my underwear, step forward, and the jolt is delivered. Like a million ants biting. Like teeth. Like the G-spot exists. Like a tiny knife, a precise pinch. Like fireworks. I can’t help it—I cry out; my underwear is flooded with perfect warmth. I like back in the grass and see stars.”

I love so much about this passage that I’ll start simply with the odd syntax of the second-to-last sentence, the em dash, the semi-colon, the instant guilt/pleasure, the reaction, the spreading gratification all there in its stilted glory. Then this use of the collar as juxtaposed later by what happens to the dog, Marky, who “got too close and his body froze and he screamed like his heart was broken, like he was being pulled apart,” this kind of rambly sentence, where as the sensations the character feels are jolty little sprints of alternating pleasure and pain and, finally, (“Like the G-spot exists. . . . Like fireworks”) explosion, spectacle, revelation.

There are babies, too—babies who kill and are killed. There’s the surreal “That Baby,” which is just a scream, and then there’s Marie Noe, who you will never forget once you meet her.

But truthfully, the story that stands out most to me is the bittersweet “Love Song,” which begins: “It was my birthday and Daddy picked me up and he was drunk and we drove to the mall and I waited at a Ruby Tuesday’s and ate me a pot of French onion soup while Daddy did the rounds at the various jewelry stores trying to sell jewelry from God knows where,” which is itself already a sad love song. This is not weepy or angry “my alcoholic father ruined my life but I’ll be better” bullshit. This is the terrified, bewildered, enamored, angry vision of a girl deeply in the middle of that shit. It’s lovely, it’s terrifying, and it’s the world slowly, dangerously coming into focus from the dark.

--Michael Goroff

Michael Goroff is a contributing editor and small press fiction staff reviewer for Barn Owl Review. He recently graduated from the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts program and still lives with his cat in Akron, Ohio, for now.

Also by Michael Goroff:

Review of The Great Frustration by Seth Fried

Review of Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls by Alissa Nutting

Review of Volt by Alan Heathcock

Review of Look! Look! Feathers by Mike Young

Review of Us by Michael Kimball

Review of How They Were Found by Matt Bell

|

|