|

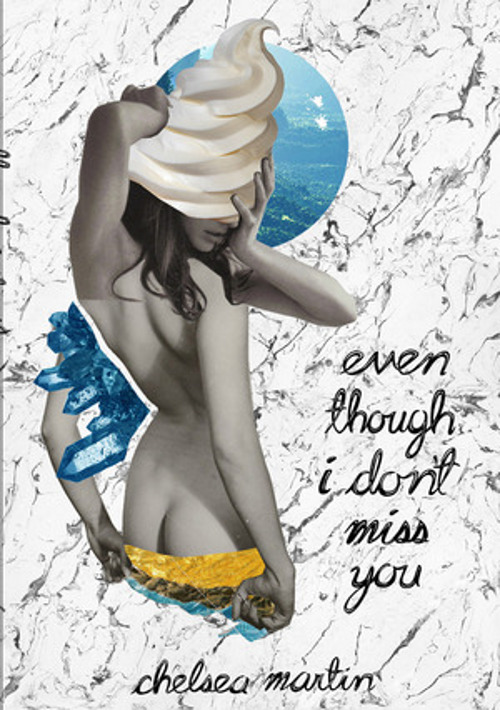

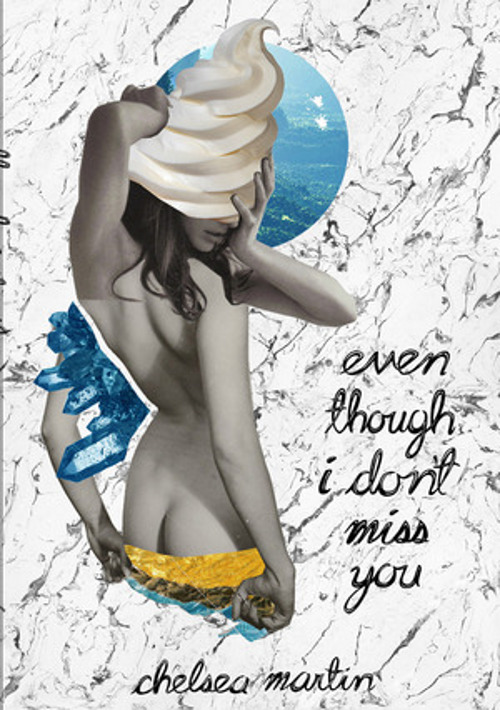

Even Though I Don’t Miss You

Chelsea Martin

Short Flight/Long Drive Books

2013

112 pages

I read Chelsea Martin’s Even Though I Don’t Miss You in a little over an hour. Then I remembered I was supposed to be reviewing, so I read it again. I alternated between laughing and feeling self-conscious. On the third read through, I finally had enough thought to establish a review.

The book is deceptively simple. The speaker calls the tiny works poems, but a better description is probably microfiction. They are short blocks of prose that often don’t even fill up a quarter of the page. The austerity of the form synthesizes beautifully with the content. They are sparse, vague, and full of potential. Over the course of one hundred pages, the narrator tells the story of a failed relationship. The book is filled with malaise and melancholy, but there are enough glimmers of joy to keep the text from wallowing. There are minor jumps in chronology that see the relationship through from beginning to end, but the overall trajectory is set in both tone and subject matter from the first few pages.

I called the writing microfiction in terms of genre, but what it feels closest to is a series of koans. Martin’s narrator is witty, sharp, and self-deprecating. She feels like she feels too acutely. She thinks she thinks too much. She has profound thoughts on pants, social networking, and heat conductivity but can’t share or communicate these ideas with her partner.

The book oscillates perfectly between the general and the specific, the universal and the individual. Stephen King writes about the “ecstasy of pure recognition” and how it makes a reader feel good. Martin does the opposite. She identifies a situation so accurately, that it makes the reader blush. Martin writes, “Being in a relationship for a very long time feels just like being single except that I can’t remember the last time I was alone for more than five hours.”

The book takes meta-turns where the narrator draws attention to the fact that she is authoring these poems for her ex-lover. It’s not just a neat postmodern trick, though. Everything is done with reason in this book. The narrator uses these meta moments to examine her own self-involvement. She struggles with her own authority. She admits, “I guess I’m still coming to terms with the fact that when I walk out of a room the story line continues in the room I just left instead of following me around like a security camera.”

There’s a great deal of empathy in the book. Martin uses simple personal pronouns, primarily I and you, to great effect. At one point, the narrator tells her lover, “Everything I said to you was so funny that I didn’t want to stop talking to you and miss any of the funny things that might come out of me.” The narrator is describing a specific situation, but the reader is going through the same thing as well in the act of reading the book. It all matches up in a synergistic way. It makes the book a delight to read. It puts the reader on edge and then invites them back to bed. It uses vagueness to defamiliarize and then draws on a moment so precise that it feels like you’ve stepped on a trap-door. It does all this and leaves the reader wanting more. The only thing to do is go back and read it all again.

--Jacob Euteneuer

Jacob Euteneuer lives in Akron, OH with his wife and son, where he is a Barn Owl Review small press fiction staff reviewer, and a candidate in the Northeast Ohio MFA. His stories and poems have appeared in Hobart, WhiskeyPaper, and Front Porch Review among others.

Also by Jacob Euteneuer:

Review of The Aversive Clause by B.C. Edwards

|

|