|

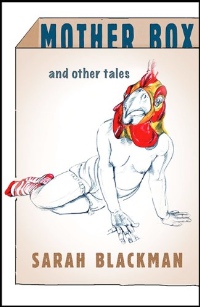

Mother Box, and Other Tales

Sarah Blackman

Fiction Collective 2

2013

224 pages

Sarah Blackman’s debut story collection Mother Box, and Other Tales is the winner of the FC2’s Roland Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize. When a book comes tagged with the label of “innovative fiction,” it can generally go in two directions: its prose will be inventive or its narratives will be wild. Blackman chooses to write clear, clean prose that makes the fabulist elements of the plot feel all the more strange. She catalogues ordinary details and then drops the moon, literally, into a dinner party. The overall effect of this style leaves the reader bewildered and grasping for more of the everyday details that once felt out of place but now are the only thing connecting the text to our world.

It’s a double edged sword. Occasionally, the stories meander and turn back on themselves in a way that is delightful. A synthesis emerges between the reader and the characters in the stories. Each is trying to make sense of the world and doing everything he or she can to hold onto their sanity. At other times, the stories fall flat and the ambiguity overtakes any sense of meaning as in the title story when the communal point of view discovers the genealogy of the main character involves cardboard boxes. All in all, this is a collection that continually challenges the reader to meet Blackman halfway. At its best, the reader is given enough guidance and is able to scale the mountain. When this happens, the view is breathtaking. In the more uneven stories, the reader ends up in the same situation as the protagonist in “Many Things, Including This”: lost in the fog and struggling for answers.

The stories in this collection vary in length from the almost-novella “The Silent Woman” to flash-fiction style pieces such as “The Cherry Tree.” Most of the stories are around ten pages long, and it is at this length where the balance between satisfied curiosity and pleasant ambiguity reaches an equilibrium.

The two stars of this collection are “A White Hat on His Head, Two Wooden Legs” and “A Beautiful Girl, A Well Loved One.” Both of these stories lay a solid foundation of fairy tale before the characters are forced to move into a contemporary world. The juxtaposition between the fantastic and the common results in a tale that is richer than either could be on its own. A girl grows up in a cottage in the woods with her mother and grandmother before she eventually grows up and takes on a high-powered business position. Where Blackman is at her best is when she is able to use language to retain the familiar plot elements of fairy tale in a present-day setting. After the girl moves out of the cottage in the woods, she is unable to shake her fairy tale upbringing. In one of the many lovingly-detailed lists throughout the books, the narrator asks what a girl needs. Snuck in between mundane items such as bras and cigarettes are “razors for shaving the fur that grows in her creases” (136). Even when the world of the Brothers Grimm is abandoned, its effects reverberate through the characters until the end of their stories.

Blackman has an eye for detail and is able to turn the mundane into the significant. Her stories are ambitious, and with everything that takes risks, it occasionally doesn’t pay off. However, when it does, it reminds the reader why he or she turned to fiction in the first place. There is power in these stories, and when they are well-told, they lodge in the reader’s brain and fill their dreams with boxes, soldiers, balls of string, and babies. It’s the kind of thing that make stories worth reading.

--Jacob Euteneuer

Jacob Euteneuer lives in Akron, OH with his wife and two sons. He is a candidate in the Northeast Ohio MFA and Editor-in-Chief of Rubbertop Review. His stories and poems have appeared in Atticus Review, Booth, and Hobart, among others.

Also by Jacob Euteneuer:

Review of Even Though I Don't Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Review of The Aversive Clause by B.C. Edwards |

|